This article will appear in the next issue of The Institute Letter.

Pluto, the ninth planet in our Solar System was discovered in 1930, the same year the Institute of Advanced Study in Princeton was founded (Pluto was originally classified as the ninth planet in the Solar System. In 2005, the International Astronomical Union decided to call Pluto a dwarf planet). While the Institute hosted more than 6000 members in the following 65 years, not a single new planet was discovered during the same time.

Finally, in 1995, astronomers spotted an object they called 51 Pegasi b. It was the first discovery of a planet in over half a century. Not only that, it was also the first planet around a Sun-like star outside our own Solar System. We now call these planets extrasolar planets, or in short, exoplanets.

As it turns out, 51 Pegasi b is a pretty weird object. It is almost as massive as Jupiter, but it orbits its host star in only 4 days. Jupiter, as a comparison, needs 12 years to go around the Sun once. Because 51 Pegasi b is very close to the star, its equilibrium temperature is very high and it is often referred to as a Hot Jupiter.

Since the first exoplanet was discovered, the technology has improved dramatically and worldwide efforts by astronomers to detect exoplanets now yield a large number of planet detections each year. In 2011, 189 planets were discovered (which is approximately the number of visiting members at the Institute that year). In 2012, 130 new planets were found. As of May 20, 2013 the total number of confirmed exoplanets is 892 in 691 different planetary systems.

Personally, I am very interested in the formation of these systems. We have so much information about every planet in our Solar System, but little is known about all those 892 exoplanets. Digging into this limited dataset and trying to find out how exoplanets obtain their present day orbits is very exciting. Many question pop up even by just looking at the first discovered exoplanet, 51 Pegasi b. Why is it a hundred times closer to its star than Jupiter? Did it form further out? Maybe it was not too different from our own Jupiter in the past? For 51 Pegasi b, we think we know the answer: Yes, it did form further away from the star where conditions such as the temperature are more favorable for planets to form. It then moved inwards in a process called planet migration. For many of the other 891 planets, the story is more complicated, especially when multiple planets are involved. The diversity of planetary systems that have been found is tremendous. We haven’t found a single systems that looks remotely similar to our own Solar System. This makes exoplanetary system so exciting to study!

To do this kind of research one needs a catalogue of all exoplanets. Several such databases exist, but they all share one fundamental flaw: they are not open. These databases are maintained either by a single person or by a small group of scientists. It is impossible to make contributions to the database if one is not part of this inner circle. This bothered me because it is not the most efficient way and it does not encourage collaboration among scientists. I therefore started a new project during my time at the Institute, the Open Exoplanet Catalogue. As the name suggests, this database, in comparison to others, is indeed open. Everyone is welcome to contribute, make corrections or add new data. Think of it being the wikipedia version of an astronomical database.

The same idea has been extremely successful in the software world. With an open source license, programmers provide anyone with the rights to study, modify and distribute the software that they have written. For free. The obvious advantages are affordability and transparency. But maybe more importantly, perpetuity, flexibility and interoperability are vastly improved by making the source code of software publicly available. The success of the open source movement is phenomenal. Every time you start a computer, open a web browser or send an e-mail, it involves programs (mostly the important ones in the background) which are open source.

The success story of open source is largely based on the wide adoption of distributed version control systems (the most popular of those tools is git, used by the Linux kernel and many other major open source projects). These toolkits allow thousands of people to work and collaborate together on a single project. Every change ever made to any file can be traced back to an individual person. This creates a network of trust, based on human relationships. Initially the concept of having thousands of people working on the same project may appear chaotic, risky or plain impossible. However, studies have shown that this kind of large scale collaboration produces software which is better (In the software world better is often measured in units of bugs per line of code) and more secure than using a traditional approach.

Astrophysics lags behind this revolution. While there are some software packages which are open source (and widely used), the idea of applying the same principles to datasets and catalogues is new. Extrasolar planets provide an ideal test case because the dataset is generated by many different groups of observers from all around the world. Observations and discoveries are evolving so quickly that a static catalogue is not an option anymore.

To get people excited about the ideas and philosophy behind the Open Exoplanet Catalogue, I started the Exoplanet Visualization Contest. It is a competition with the goal to come up with stunning and creative ways to visualize exoplanet data. We set no restrictions to the kind of submission. The only requirement was that each submission had to use real data from the Open Exoplanet Catalogue. This led to an extremely diverse set of submissions. For example, we received publication-grade scientific plots, artistic drawings of potentially habitable exo-moons and an interactive web-site. One participant went as far as designing a wearable vest with built-in microcontrollers and displays that show exoplanet data. Thanks to a generous outreach grant from the Royal Astronomical Society in London, we were able to give out prizes to the best submissions. With the help of Scott Tremaine, Dave Spiegel and Dan Fabrycky, two winners were chosen.

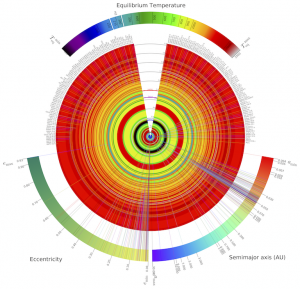

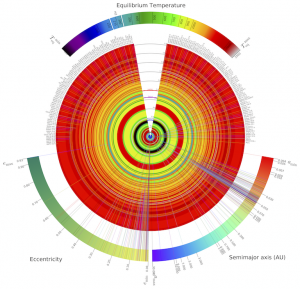

The second prize went to Jorge Zuluaga from Antioquia, Colombia. He designed a new way to present exoplanet data such as planetary sizes and equilibrium temperatures.

Those are of particular interest when it comes to determining whether a planet is potential habitable or not. His submission, the so called Comprehensive Exoplanetary Radial Chart is shown above. It illustrates the radii of exoplanets filled with colors representing their approximate equilibrium temperatures.

The chart also shows information on planetary orbit properties, size of host stars and potentially any other variable of interest.

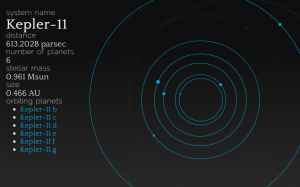

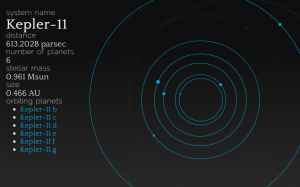

The winner of the contest was Tom Hands, a PhD student from Leicester. He wrote an interactive website ExoVis that visualizes all discovered planetary systems. The project makes use of HTML5, Javascript, jQuery and PHP. One can search for planets, study their orbital parameters and compare them to other systems, all within a web browser.

The Open Exoplanet Catalogue is a very new project. The crucial issue is to reach a large number of regular contributors. Then, the quality of the dataset will outperform all closed competitors in the long run in the same way wikipedia is now much more widely used than the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Looking at the success so far, I am optimistic about the future.

More information about the Open Exoplanet Catalogue, its workflow and data format is available at openexoplanetcatalogue.com.